The Vintage Roots Guide to English Wine

The History of English Wine… (not quite) briefly!

We have to thank the Romans…

It’s impossible to move a few feet in the world of wine without bumping into the Romans and their impact on vinous history. There is strong evidence of a healthy wine drinking culture pre-Roman occupation in the UK but the consensus is that it was the Romans who introduced the vine to Great Britain .

The Romans were in the UK for 300 years and their occupation was followed by invasions from the Jutes, Angles and Saxons, during which time the vineyards established by the Romans were most likely left to ruin.

The Romans were in the UK for 300 years and their occupation was followed by invasions from the Jutes, Angles and Saxons, during which time the vineyards established by the Romans were most likely left to ruin.

The Influence of Christianity on English wine

Come the sixth century there is evidence of vineyards again being established but when the Vikings came two centuries later, they destroyed many monasteries and again, the vineyards were lost. .

Along came King Alfred and with him Christianity. Wine was made again from grapes grown in the monastery vineyards in the southern regions.

When the Normans came in 1066 with William the Conqueror, the French Abbots and their monks, there was a flurry of vine growing and wine making activity in England. The soldiers and courtiers demanded wine on a daily basis and their needs had to be met. In the Domesday Book (1085-6) there are records of vineyards in 42 locations.

At this time the vineyards were not just under the stewardship of the monasteries but were also in the ownership of the nobles. The south-east coast, Somerset, Gloucestershire, Herefordshire and Worcestershire were the most important areas for vine growing at that time.

Although wine was being imported at this time, solutions for preserving wine during travelling time and warmer summer temperatures had yet to present themselves and so the home wines fared well, having less distance to travel and fewer opportunities to spoil.

After the Middle Ages

So what caused the decline from the Middle Ages to the resurgence in the twentieth century? The Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536 is clearly a major factor but there were other reasons. Records suggest that the climate changed, the summers becoming cooler and wetter and the winters increasingly mild. This made it harder for the grapes to ripen and left the vines more open to disease.

Secondly, wine from abroad was arriving faster, less expensively and more reliably. The wine coming in was simply better than what could be made at home.

Secondly, wine from abroad was arriving faster, less expensively and more reliably. The wine coming in was simply better than what could be made at home.

Last, but by no means least, was the Black Death in the fourteenth century which dramatically reduced available workforce for the vineyards. There was also an understandable shift in agricultural demands at the time with short-term cash crops more desirable than vines.

And so we became a nation whose skills lay in shipping, bottling and storing wine. We became a nation of importers.

English Vineyards in the 17th and 18th centuries

Still, the vine growing itch hadn’t left British shores for good… The famous botanist, John Tradescant planted vineyards at Lord Salisbury’s estate in Hertfordshire in the 1600s. The Hon Charles Hamilton planted vines at Painshill Place in Cobham, Surrey in 1740 and there is still a producing vineyard at the site today. In the late nineteenth century Lord Bute at Castle Coch in Wales had several acres turned over to vine.

English Wine in More Modern Times

The resurgence in vine growing and winemaking in Great Britain started in the 1950s when the first commercial vineyard of modern times was planted at Hambledon in Hampshire.

Today’s British winemakers have much to thank the viticulturalist, Ray Barrington Brook for. He trialled and tested many hundreds of grape varieties at his research station in Surrey for over 25 years. It was he who identified the varieties that would work well in home soils. He also looked into vinification methods and looked to identify the best techniques.

Ray Brook joined forces with Edward Hyams and George Ordish (two equally passionate and wine-knowledgeable Englishman) to plant the Hamledon vineyard.

Today there are vineyards across the counties of England and Wales and you will even find some plantings in Scotland.

The Great British wine industry is booming! Investment is coming from home and abroad with world-famous Champagne houses investing in land on the south coast. In 2019 there were 658 commercial vineyards and 164 wineries. There are three million vines planted in Great Britain… a 194% increase in the last ten years!

This history is a shortened version of what appears on the hugely information www.winegb.co.uk website. Please visit the site for more detailed information.

English Grape Varieties… Or should we say, the varieties most widely planted in England and Wales

Here’s an interesting fact. The French red variety, Pinot Noir is the most widely planted here. We have 1063 hectares of it, which is almost one third of all vineyard plantings.

Chardonnay comes a very close second at 1034 hectares and then there’s quite a big drop to the third most commonly found variety, Pinot Meunier (394 hectares)

The observant will notice that these are the three varieties most commonly found in Champagne. It is not a big surprise; much of our south coast terroir is similar to that found in Champagne.

Correspondingly 69% of wine production in England and Wales is sparkling.

You will find still English wines – red wines, rosé wines and white wines – made from these grapes but you will also see varieties such as Bacchus, Seyval Blanc, Pinot Gris, Reichensteiner and Madeleine Angevine mentioned. Just as is the case with all countries, the grapes grown here have been selected for their ability to perform well in our climate.

You’ll often find Bacchus referred to as the ‘Sauvignon Blanc of English wine’ because of its aromatic qualities.

Pinot Gris (maybe more familiar to you as Pinot Grigio) is still only planted in very modest quantities but early signs are encouraging.

Seyval Blanc and Reichensteiner are both crossings, again selected for their ability to ripen well in our summers. Most commonly these are used in blends.

Wine Producing Regions in England and Great Britain

The greatest proportion of vineyards in Great Britain are found in the South East with 78% of total plantings.

The South West has 13%, East Anglia 4%, Wales 1% and the remainder of the UK 6%.

We do not yet have regional and appellation system like those found in other European countries. However, wine producers in England and Wales can apply for the EU indicators of quality and authenticity that are PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) and PGI (Protected Geographical Indication).

Only the wines produced in the county of Sussex are able to apply for the designation called, ‘Sussex Quality Wine’, which is still awaiting final approval form the European Commission.

English Sparkling Wine: A success story… with a climate change caveat

One of the world’s finest and most thoughtful wine writers, Andrew Jefford wrote an excellent piece on the success of English Sparkling Wine in the October 2019 edition of Decanter Magazine. You can read it in full here but this segment captures the English sparkling wine story perfectly:

“It took two moneyed Americans, Stuart and Sandy Moss, to give sparkling wine a try in the UK, to do it properly, and open everyone’s eyes to the exciting potential. As Stephen Skelton MW recounts in his recently published The Wines of Great Britain, when the Moss’ first three releases each stormed to competition victory: ‘Most of us realised that things would never be the same again and that the days of German variety-based still wines were over.’ Nyetimber, the sparkling wine brand they created, is (under its present owner Eric Heerema) well on the way to becoming the UK equivalent of a medium- sized Champagne house. It has 258ha planted in a range of sites, and the ambition to go on up beyond 300ha or so, with annual production of two million bottles.

The second reason for the turnaround, and for the fact that viticulture is now one of the most buoyant and fast-expanding segments of UK agriculture in general, is climate change. If we can now grow satisfactory Chardonnay and Pinot Noir for sparkling wine purposes, it’s because (as Skelton stresses) summer days increasingly cross the 29°C or 30°C threshold, because summer nights are warmer, because mean July temperatures across southern Britain now routinely approach 18°C rather than struggling to crest 15°C. That wasn’t true in the 1980s. This is sudden and dramatic. Any climate change that can be measured over half a human lifetime is, by comparison with customary planetary rates of meteorological change, much faster than a gallop. It also reminds us that wine is climate litmus.

I’m happy that UK wine production is flourishing. We shouldn’t forget, though, that millions will suffer terribly from the same phenomena; indeed the sheer disorderliness of climate change, so clearly exhibited in the 2017 Champagne vintage, may come to taunt all wine-growers. The carbon footprint of the wine trade, with its fermentative carbon dioxide, its wine miles and its addiction to glass bottles, remains troubling. We can’t overlook these inconvenient truths, no matter how locally welcome some of the effects of climate change might be.” Andrew Jefford, Decanter Magazine, October 2019

Styles of English Red Wine and English White Wines and Foods to enjoy them with

Still wines make up one-third of wine production in England and Wales and by far the greatest proportion of that is white wine.

English red wine is a challenge because our climate, though changing, isn’t typically sunny and warm enough for the lengths of time that it takes to ripen red grapes to a level that makes juicy, characterful reds. There are, of course, notable exceptions and we’re lucky to have an allocation of the Limney Estate Diamond Fields Pinot Noir 2017. Normally the grapes grown at the Diamond Fields site are for his sparkling wines but the fruit was so good in 2017 that Will Davenport chose to make this hugely stylish red.

Original price was: £23.00.£20.70Current price is: £20.70.

There are some very lovely English red wines to be had but we think it’s the rosé wines that shine. Lighter, yes but they embrace the freshness and red berry fruits of varieties like pinot noir and pinot meunier. Try the deliciously delicate Silent Pool Rosé from Albury Organic Vineyard with a plate of fine English asparagus.

English white wine can offer some exciting alternatives to those being imported from Europe. Bacchus, famous for its Sauvignon Blanc-like qualities yields aromatic, expressive wines. Forty Hall Bacchus captures the grape’s natural exuberance and is a treat with a gentle Thai curry and vegetarian speltotto.

Blends are very common in English white wines because they allow the winemaker to pick the best of the vineyard crop, discarding those varieties that maybe haven’t done so well in a particular vintage. Described as “complex, a tapestry of flavours and a filigree-threaded diamond-cut texture. Beautiful wine” (www.jancisrobinson.com), the Davenport Horsomeden Dry White is a cracking blend. In 2018 it is a blend of Bacchus, Faber, Huxelrebe, Ortega and Siegerrebe! Delicious with a traditional cheese soufflé or a roast chicken supper.

Original price was: £18.50.£16.65Current price is: £16.65.

Some Interesting and Fun Facts about English Wine

- The acreage under vine in the UK has tripled since 2000

- Organic estate, Davenport Vineyards won the ‘Champion Team Trophy’ at the UK’s first Vine Pruning Competition in 2019

- Two of the biggest names in Champagne – Tattinger and Pommery – have bought land in England (Kent and Hampshire respectively for vine growing)

- The first certified organic vineyard in England was planted in 1979 at Sedlescombe

- One third of wine made in England is sparkling

- In 2018 Head Winemaker at England’s Nyetimber, Cherie Spriggs won ‘Sparkling Winemaker of the Year” at the International Wine Challenge.

What makes English wine so expensive?

It’s a tricky question to dodge…! In a nutshell, English wine can appear more expensive than their foreign counterparts because land and costs of production are often much higher. Vineyards often don’t deliver the same sort of yields and despite climate change, there are still weather challenges to negotiate.

A better question to ask might be, is English wine worth the money?! Yes, we say. The quality is sky-high (just look at the gold medals we’ve scooped up at home and abroad in recent years) and it is great to support home produced goods. The English wine industry plays an important part in our economy. It’s not just the vineyards that are an important employer, the associated wine tourism business also creates jobs and creates wealth.

English Organic Wine Producers

Wines of Great Britain (www.winegb.co.uk) is an organisation in its infancy. So, rock solid data on organic wine production in GB isn’t easy to find! . But here is what we know about our English organic wine producers.

The critically acclaimed wines from Will Davenport come from vineyards that have been organic since 2000.

Try the Davenport Limney Estate Sparkling… Outstanding.

Original price was: £31.00.£27.90Current price is: £27.90.

The largest organic estate in the UK is Oxney, which is located between Rye and Tenterden in East Sussex. They have an impressive 14 hectares certified organic.

We love the Oxney Pinot Noir Rosé which scored an impressive 16.5/20 from Jancis Robinson, MW.

£25.00

Albury may be small but they are big on organics and biodynamics and inspired by some of the great biodynamic vineyards of the world, they are following their examples.

£38.00

Forty Hall Vineyard is an inspiring project based on the 170 acre organic mixed farm in Enfield, north London! Run and managed by local people as a not-for-profit social enterprise, it was founded in 2009 by wine enthusiast and social entrepreneur Sarah Vaughan-Roberts.

If England has a ‘classic’ white grape, then it has to be Bacchus. Forty Hall make a great one!

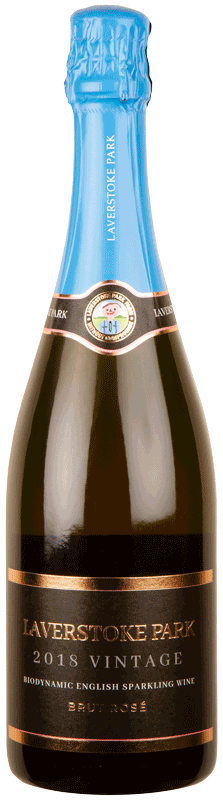

Like Albury, Laverstoke Park Farm is certified biodynamic and the nine-hectare vineyard is just 16 miles from Vintage Roots HQ.

For a simply divine English Sparkling Pink, look no further than Laverstoke’s Biodynamic Vintage Rosé.

Original price was: £42.00.£37.80Current price is: £37.80.

English Wine Week 2020: Saturday, 23 May until Sunday 31 May

English Wine Week is a great opportunity to get to know our wines better with vineyards and outlets across the country opening their doors to you, offering the opportunity to taste the wines and see where and how they are made.

Keep an eye out nearer the time to see how your local vineyard or wine merchant will be celebrating English wine week.